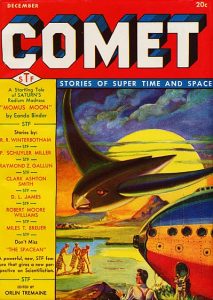

A lengthy period of contraction followed the science-fiction and fantasy pulp boom of 1939. With the United States about to enter the Second World War and paper rationing limiting magazine production, the only new magazines to appear before the conflict’s end were the short-lived Comet, Cosmic Stories and Stirring Science Stories, plus rebound copies of Amazing Stories and Fantastic Adventures.

A lengthy period of contraction followed the science-fiction and fantasy pulp boom of 1939. With the United States about to enter the Second World War and paper rationing limiting magazine production, the only new magazines to appear before the conflict’s end were the short-lived Comet, Cosmic Stories and Stirring Science Stories, plus rebound copies of Amazing Stories and Fantastic Adventures.

A British magazine entitled New Worlds was the first new science-fiction magazine to appear following World War II. Although it first appeared in 1946, it didn’t come into its glory until Michael Moorcock became editor in 1964. New Worlds would run for 222 issues and become the focus of science fiction’s “New Wave.” A companion magazine, Science Fantasy (later titled Impulse), premiered in 1950.

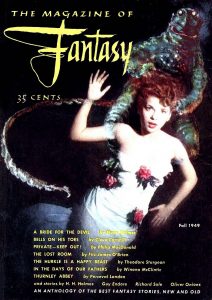

The first U. S. magazine to appear after the war was Avon Fantasy Reader. Edited by Donald A. Wollheim, it was primarily a reprint magazine. The first new fantastic magazine would wait until 1949 when The Magazine of Fantasy–the “and Science Fiction” was added later–premiered in the fall. Originally edited by Anthony Boucher and J. Francis McComas and published by Lawrence Spivak, its founders sought to move away from pulp concepts, asking its writers for stylish fiction “that was up to the literary standards of the slick magazines.” Still published today, F&SF–as it has become known–has greatly helped both science fiction and fantasy to mature as genres. It is still published today.

The first U. S. magazine to appear after the war was Avon Fantasy Reader. Edited by Donald A. Wollheim, it was primarily a reprint magazine. The first new fantastic magazine would wait until 1949 when The Magazine of Fantasy–the “and Science Fiction” was added later–premiered in the fall. Originally edited by Anthony Boucher and J. Francis McComas and published by Lawrence Spivak, its founders sought to move away from pulp concepts, asking its writers for stylish fiction “that was up to the literary standards of the slick magazines.” Still published today, F&SF–as it has become known–has greatly helped both science fiction and fantasy to mature as genres. It is still published today.

Ray Palmer, most remembered today for his trumpeting of the Shaver Mystery in Amazing Stories and Fantastic Adventures, began publishing a couple of fantastic magazines around 1950. Although his first, Other Worlds, would publish a number of top-notch stories by Ray Bradbury, Gordon Dickson, Wilson Tucker, and others, Palmer would eventually convert it into a magazine about flying saucers. His other magazine was Imagination. It was sold to another publisher following its second number. Lasting for over sixty issues, Imagination published hurriedly written hack fiction by Randall Garrett, John Jakes, Frank M. Robinson and Robert Silverberg, all hiding behind pseudonyms.

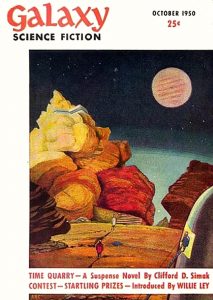

In the fall of 1950, World Editions introduced Galaxy Science Fiction, a digest magazine that paid its authors a minimum of three cents a word. Edited by H. L. Gold, the magazine serialized Alfred Bester’s “The Demolished Man” and Robert A. Heinlein’s “The Puppet Masters,” and published shorter works such as Ray Bradbury’s “The Fireman” (later expanded to become Fahrenheit 451), Damon Knight’s “To Serve Man,” and Fritz Leiber’s “Coming Attraction,” all in its first year. In 1953, Galaxy shared the first Hugo for Best Magazine with Campbell’s Analog. Later edited by Frederik Pohl, Jim Baen, and others, Galaxy ran for a total of 254 issues with its final issue appearing in 1980. Like F&SF, Galaxy was a leader in the movement to bring a more human element to science fiction.

In the fall of 1950, World Editions introduced Galaxy Science Fiction, a digest magazine that paid its authors a minimum of three cents a word. Edited by H. L. Gold, the magazine serialized Alfred Bester’s “The Demolished Man” and Robert A. Heinlein’s “The Puppet Masters,” and published shorter works such as Ray Bradbury’s “The Fireman” (later expanded to become Fahrenheit 451), Damon Knight’s “To Serve Man,” and Fritz Leiber’s “Coming Attraction,” all in its first year. In 1953, Galaxy shared the first Hugo for Best Magazine with Campbell’s Analog. Later edited by Frederik Pohl, Jim Baen, and others, Galaxy ran for a total of 254 issues with its final issue appearing in 1980. Like F&SF, Galaxy was a leader in the movement to bring a more human element to science fiction.

Given the success of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction and Galaxy Science Fiction, other publishers tried to cash in on the growing market. Most of them quickly folded. Some of the more notable magazines introduced during the fifites included If—particularly when it was edited by Frederik Pohl; Nebula Science Fiction—a Scottish magazine; Fantastic—started by Howard Browne for Ziff-Davis; Fantastic Universe—nicknamed “the poor man’s” F&SF; Beyond Fantasy Fiction—a short-lived fantasy companion to Galaxy Science Fiction; and Imaginative Tales—a companion to Imagination.

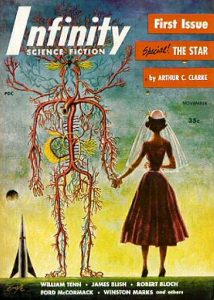

At the dawn of the space race, ten new science-fiction magazines entered the market. The best was Infinity Science Fiction. Edited by Larry Shaw, it published some good stories by authors such as Isaac Asimov, James Blish, Arthur C. Clarke, Damon Knight and C. M. Kornbluth. Other longer-lived magazines to premier during this time included Infinity Science Fiction, Satellite Science Fiction, and Super-Science Fiction. Although nearly fifty British and American science-fiction and fantasy magazines were introduced during the fifties, only four of the fifty–Galaxy Science Fiction, Science Fantasy, If, and Fantastic—lasted beyond 1960.

At the dawn of the space race, ten new science-fiction magazines entered the market. The best was Infinity Science Fiction. Edited by Larry Shaw, it published some good stories by authors such as Isaac Asimov, James Blish, Arthur C. Clarke, Damon Knight and C. M. Kornbluth. Other longer-lived magazines to premier during this time included Infinity Science Fiction, Satellite Science Fiction, and Super-Science Fiction. Although nearly fifty British and American science-fiction and fantasy magazines were introduced during the fifties, only four of the fifty–Galaxy Science Fiction, Science Fantasy, If, and Fantastic—lasted beyond 1960.

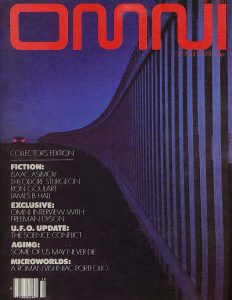

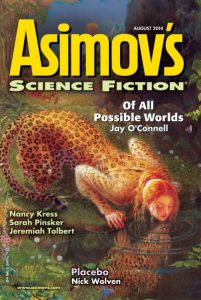

Although science fiction continued to mature after 1960, the genre increasingly turned to low-priced and portable paperback books to extend its reach. Except for the reprint digests—Magazine of Horror and Startling Mystery Stories—little of note appeared in the form of a new magazine until Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine debuted in the spring of 1977. Still running today, it will soon publish its 463rd issue. Other notable magazines from the last quarter of the twentieth century are Omni—a slick companion to Penthouse that sometimes topped a million in circulation and published science articles alongside science-fiction stories; Rod Serling’s The Twilight Zone Magazine—a companion to the men’s magazine Gallery, it sometimes sold more than 125,000 copies and featured a mix of traditional supernatural fiction and movie and television features; Interzone—a British magazine started in the spring of 1982 and originally modeled after Michael Moorcock’s New Worlds, it continues to be published today; Aboriginal Science Fiction—a magazine that debuted in 1986 and published many new writers; and Absolute Magnitude (originally entitled Harsh Mistress)—a semiprofessional magazine that debuted in the spring of 1993 and published “hard science fiction with a strong human element.”

Although science fiction continued to mature after 1960, the genre increasingly turned to low-priced and portable paperback books to extend its reach. Except for the reprint digests—Magazine of Horror and Startling Mystery Stories—little of note appeared in the form of a new magazine until Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine debuted in the spring of 1977. Still running today, it will soon publish its 463rd issue. Other notable magazines from the last quarter of the twentieth century are Omni—a slick companion to Penthouse that sometimes topped a million in circulation and published science articles alongside science-fiction stories; Rod Serling’s The Twilight Zone Magazine—a companion to the men’s magazine Gallery, it sometimes sold more than 125,000 copies and featured a mix of traditional supernatural fiction and movie and television features; Interzone—a British magazine started in the spring of 1982 and originally modeled after Michael Moorcock’s New Worlds, it continues to be published today; Aboriginal Science Fiction—a magazine that debuted in 1986 and published many new writers; and Absolute Magnitude (originally entitled Harsh Mistress)—a semiprofessional magazine that debuted in the spring of 1993 and published “hard science fiction with a strong human element.”

Today, science fiction and fantasy have, by and large, achieved the respectability they long sought. At the same time, competition from a range of media including paperback books, movies, television, video games, e-books, and the Internet, has vastly diminished the scope of magazine fantasy and science fiction. The major science-fiction and fantasy magazines in the print format–Analog Science Fiction and Fact, Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine, Interzone, and The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction–have seen their circulations shrink tremendously. Nevertheless, it cannot be denied that contemporary science fiction and fantasy owe a great deal to the magazines of the past—The Strand, Pearson’s Magazine, Argosy, The All-Story, Weird Tales, Amazing Stories, Astounding Science-Fiction, Galaxy Science Fiction, and countless others. Without them, where would science fiction and fantasy be today?

Today, science fiction and fantasy have, by and large, achieved the respectability they long sought. At the same time, competition from a range of media including paperback books, movies, television, video games, e-books, and the Internet, has vastly diminished the scope of magazine fantasy and science fiction. The major science-fiction and fantasy magazines in the print format–Analog Science Fiction and Fact, Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine, Interzone, and The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction–have seen their circulations shrink tremendously. Nevertheless, it cannot be denied that contemporary science fiction and fantasy owe a great deal to the magazines of the past—The Strand, Pearson’s Magazine, Argosy, The All-Story, Weird Tales, Amazing Stories, Astounding Science-Fiction, Galaxy Science Fiction, and countless others. Without them, where would science fiction and fantasy be today?

To learn more about the images used in this post, click on the illustrations. Click here for references consulted for this article.

The cover for Asimov’s Science Fiction is by Kinuko Craft and copyright © 2014 by Penny Publications LLC/Dell Magazines.

We hope you’ve enjoyed this discussion of magazine science fiction. If you’d like to read the unabridged version of the article–entitled “Science Fiction and the Pulps: A Genre Evolves”–it will be appearing in the PulpFest 2014 program book, The Pulpster. All you have to do to get a copy of the book is to become a member of the convention. It will take place from August 7 – 10 in Columbus, Ohio.

For those who cannot get to Columbus in August–although we’d love to see you–a supporting membership will be available that will entitle you to a copy of The Pulpster. You can register to become a regular or supporting member of the convention by visiting our registration page.

If copies are still available after the conclusion of the convention–quantities are limited–they will be available for purchase from Mike Chomko, Books. Visit our program book page to learn how to place your order.