Ted White and the Golden Age of AMAZING

The title of Ian Dury’s record “Sex and Drugs and Rock and Roll” often comes to mind when I think of science fiction from the early 1970s, especially when I think of AMAZING STORIES. Let me explain, starting with the rock and roll . . . but first, some background.

The title of Ian Dury’s record “Sex and Drugs and Rock and Roll” often comes to mind when I think of science fiction from the early 1970s, especially when I think of AMAZING STORIES. Let me explain, starting with the rock and roll . . . but first, some background.

Ted White, the new editor of AMAZING STORIES and its sister title FANTASTIC, took up his duties in October 1968. Unlike his immediate predecessors, Barry Malzberg and Harry Harrison, White was at heart a science-fiction fan: he had just won the 1968 Hugo Award as Best Fan Writer. One would have to go back to Raymond Palmer in the 1940s to find another editor of the magazine who was rooted in sf fandom. White had been born in February 1938, a few months before Palmer took the helm of AMAZING, and had grown up on a diet of Palmer’s later magazine OTHER WORLDS. It was Palmer’s style of editing that most influenced White’s own. For the first time in almost thirty years, AMAZING had the chance to develop a character.

White had already gained some editing experience before taking over at AMAZING. From 1963 to 1968 he had worked as assistant editor (later associate editor) of THE MAGAZINE OF FANTASY & SCIENCE FICTION, initially under Avram Davidson and then under Edward Ferman. He had also served a term as associate editor at Lancer Books, under Larry Shaw. In 1966 he tried to launch his own magazine, called STELLAR, but the financial burden proved too heavy. Some of the stories he had selected for that abortive magazine now had a chance to surface in AMAZING and FANTASTIC.

In addition, White was a writer. He wrote for several music magazines and had a particular passion for jazz and rock music (we’re getting to the rock-and-roll connection, but not quite yet). He also wrote science fiction, mostly of the fantastic adventure kind. Novels such as PHOENIX PRIME (1966) and its sequel THE SORCERESS OF QAR (1968) betray a variety of pulp influences, not least those of Edgar Rice Burroughs and Robert E. Howard. But White’s style was also molded by the techniques emerging from the New Wave of the 1960s. White’s tastes were not restricted to either school of science fiction. He liked the best of both.

In his first editorial for AMAZING STORIES, in the May 1969 issue, he likened the development of the New Wave in science fiction to the 1960s revolution in rock music (now we’re there), and the emergence of heavy metal and acid rock. White pointed out that this music was able to coexist beside the more melodic rhythms of the Beach Boys and other styles of music. It was also important to recognize that heavy rock was drawing upon its roots, in rhythm and blues, to express its new voice.

He saw no reason why science fiction should not follow the same pattern. Not only could all forms of science fiction exist side by side — the traditional alongside the modern — but the modern had itself developed from science fiction’s roots. By publishing both forms of sf in AMAZING, White could make it possible for the old and the new to influence each other.

He saw no reason why science fiction should not follow the same pattern. Not only could all forms of science fiction exist side by side — the traditional alongside the modern — but the modern had itself developed from science fiction’s roots. By publishing both forms of sf in AMAZING, White could make it possible for the old and the new to influence each other.

As examples of this policy, White emphasized two new stories. The first was the latest Star Kings novelette by Edmond Hamilton, “The Horror from the Magellanic.” This series, wherein the mind of twentieth-century John Gordon swaps bodies with a man from two hundred millennia in the future, was highly derivative of Burroughs’s Martian novels. The first of the series, “The Star Kings,” had appeared in AMAZING back in September 1947, and while Hamilton was now writing better than ever, the story and plot line were pure unadulterated pulp adventure.

The second example started in the following issue (July 1969). Robert Silverberg’s new serial, “Up the Line,” was a lighthearted but ingenious time-travel adventure, in which a Time Courier changes the past and finds himself on the run from the Time Police. Looking back now from the vantage point of more than twenty years in the future, the story seems fairly mundane, but at the time it was a fresh treatment of an old theme. It proved very popular and was the runner-up to Ursula K. Le Guin’s THE LEFT HAND OF DARKNESS for the 1970 Best Novel Hugo Award, overcoming such competition as Kurt Vonnegut’s SLAUGHTERHOUSE-FIVE, Piers Anthony’s MACROSCOPE, and Norman Spinrad’s trend-setting BUG JACK BARRON.

Although the Swinging Sixties were almost gone and flower power was fading fast, the influence of psychedelia had left its mark on Ted White, and this influence now infiltrated AMAZING STORIES. But White first had to overcome the legacy of the last few years.

When Sol Cohen purchased the magazines in 1965, he instigated a reprint policy, taking advantage of the fact that AMAZING‘s previous publishers had bought second serial rights to the stories. Cohen could thus fill the magazines with reprints and make no further payments to the authors, saving around $8,000 a year minimum. His editors, though, had insisted that each issue contain at least one or two new stories. The best of these original works were serials. The stories were often short and, as time went on, seldom significant.

Ted White sought to change that. With the November 1969 AMAZING he was able to proclaim that thereafter issues would contain only one reprint, and that as a bonus to an otherwise full issue of new stories. The use of a smaller typeface meant that the magazine contained at least 70,000 words of new material, the equivalent of any other sf magazine.

Cohen had siphoned the reprints into a number of all-reprint magazines. He had already established GREAT SCIENCE FICTION, THE MOST THRILLING SCIENCE FICTION EVER TOLD, (later retitled THRILLING SF ADVENTURES, and SCIENCE FICTION CLASSICS). These were now supplemented by SPACE ADVENTURES, STRANGE FANTASY, SCIENCE FANTASY, and others, all of which drew indiscriminately upon the best and worst fiction from AMAZING, FANTASTIC, and FANTASTIC ADVENTURES, without payment to the writers. Even though the separateness of the reprint magazines from AMAZING and FANTASTIC allowed White to develop new fiction in those two titles, the cheap production and content of the reprint magazines gave science-fiction magazines a poor image. Most of these titles were short-lived, although SCIENCE FICTION ADVENTURES lasted until 1974, when it was absorbed into THRILLING SCIENCE FICTION, which survived for two more issues.

Cohen had siphoned the reprints into a number of all-reprint magazines. He had already established GREAT SCIENCE FICTION, THE MOST THRILLING SCIENCE FICTION EVER TOLD, (later retitled THRILLING SF ADVENTURES, and SCIENCE FICTION CLASSICS). These were now supplemented by SPACE ADVENTURES, STRANGE FANTASY, SCIENCE FANTASY, and others, all of which drew indiscriminately upon the best and worst fiction from AMAZING, FANTASTIC, and FANTASTIC ADVENTURES, without payment to the writers. Even though the separateness of the reprint magazines from AMAZING and FANTASTIC allowed White to develop new fiction in those two titles, the cheap production and content of the reprint magazines gave science-fiction magazines a poor image. Most of these titles were short-lived, although SCIENCE FICTION ADVENTURES lasted until 1974, when it was absorbed into THRILLING SCIENCE FICTION, which survived for two more issues.

White still had to use one reprint an issue in AMAZING, until he could do away with them altogether beginning with the March 1972 issue. For the immediate future, White was also forced to use cover paintings purchased cheaply from European magazines, but he made the best of this situation by commissioning authors to write stories around them. The first was Greg Benford’s “Sons of Man” in the November 1969 issue. Set at the end of the 1990s, the story links the discovery of a wrecked spacecraft on the Moon with the fabled Bigfoot. Benford was still a relatively new writer with his reputation yet to be made, and this story is far from his best, though the ending is poignant. The same issue saw the start of Benford’s series of scientific articles under the general title of “The Science in Science Fiction,” written with fellow physicist David Book.

Of some significance in the November 1969 AMAZING was the start of Philip K. Dick’s new serial, “A. Lincoln, Simulacrum,” better known by its book title, WE CAN BUILD YOU. This isn’t one of Dick’s most notable novels, but it is a key one in the understanding of his fears about the future. Its significance is related more to the type of reader Dick was likely to attract to the magazine. At this time Dick was establishing his following among the drug culture, many of whose members had been attracted by his enigmatic classic, THE THREE STIGMATA OF PALMER ELDRITCH. While White was not going out of his way to pander to the growing drug culture, he did seem to have a close affinity with it. This was evident from an article, “Science Fiction and Drugs,” which White wrote pseudonymously in the June 1970 FANTASTIC. He believed we were entering the “psychedelic seventies,” in which alcohol would be out and drugs would be in. White didn’t overtly promote the free use of drugs in this article, but he did clearly favor drugs over alcohol, and suggested that science fiction needed to consider how the possible legalization of some drugs might affect the future.

White was open to a greater liberalization of science fiction, in line with what was happening to youth nationwide. He saw science fiction as a vehicle to push back the barriers of the “establishment” with no suppression of soft drugs, “healthy sex,” or free expression. Both AMAZING STORIES and FANTASTIC were becoming closer to “hippie” sf magazines than anything else in science fiction.

In hindsight, there may be some relationship between that fact and the work of Ursula K. Le Guin at this time. Her straightforward drug-image story, “The Good Trip,” appeared in FANTASTIC (August 1970), and AMAZING serialized her novel of dream-worlds, “The Lathe of Heaven” (March and May 1971). This book, about a patient whose dreams can alter reality, reads like a tribute to Philip K. Dick, which is further emphasis of the development of AMAZING into a magazine where the fiction challenged the very fabric of this world and beyond. The novel was both a Nebula and a Hugo Award nominee.

White strove to attract good fiction and new writers to the magazines. AMAZING had been in a wilderness for the last five years, and White was having a hard time attracting writers. Because he was paying the lowest rates in the field, he knew he wouldn’t have first shot at the best fiction around, but he might have a chance at some of the best experimental fiction, which had no ready market elsewhere, and thereby attract those writers who didn’t otherwise click with the establishment. One such writer was Piers Anthony.

White strove to attract good fiction and new writers to the magazines. AMAZING had been in a wilderness for the last five years, and White was having a hard time attracting writers. Because he was paying the lowest rates in the field, he knew he wouldn’t have first shot at the best fiction around, but he might have a chance at some of the best experimental fiction, which had no ready market elsewhere, and thereby attract those writers who didn’t otherwise click with the establishment. One such writer was Piers Anthony.

Today, Anthony’s name is closely associated with his humorous, pun-ridden fantasies set in the Oz-like world of Xanth, and he is regarded by some (unfairly) as a hack. Twenty years ago, Anthony was emerging as one of the more original and challenging writers of science fiction, especially with his novels CHTHON and MACROSCOPE. At this early stage in his career he was having problems finding a regular market for his material. Typical was the plight of his novel “Hasan,” a fantasy modeled on an episode in THE ARABIAN NIGHTS, which had received a dozen rejections from publishers. Anthony became more entrepreneurial and had the manuscript reviewed in the amateur magazine SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW. Here it came to the attention of Ted White, who asked to see it and within three weeks had bought it for FANTASTIC (it was serialized in the December 1969 and February 1970 issues). This original way to both sell and acquire material shows how White’s proximity to fandom had its advantages.

Pleased with the reception of “Hasan,” Anthony offered White his next novel, “Orn.” This was the sequel to OMNIVORE, but Anthony had been having problems with his publisher over the novel. It was serialized in the July and September 1970 issues of AMAZING. These two novels coming out so close together brought attention to the diversity of Anthony’s work and the detail in his research and story development. I like to think they helped boost Anthony’s reputation, which was struggling to establish itself in the book market. I can certainly attest to my own feelings at that time; it was the reading of these two novels that clinched Anthony in my mind as a writer of note. I suspect these sales also boosted Anthony’s confidence in trying times. He has gone on record as regarding White as “an excellent editor.”

Other writers who refused to be categorized but who seemed at home in Ted White’s world began to appear, among them Richard A. Lupoff, Barry N. Malzberg, David R. Bunch, R. A. Lafferty, Alexei Panshin, Christopher Priest, James Tiptree, Jr., Avram Davidson, and Philip José Farmer. All offered their offbeat style of story, which had had a chance to mature since the experimental days of the mid-1960s when Michael Moorcock’s NEW WORLDS led the revolution in speculative fiction. Not only were these stories more acceptable to the reader by the early 1970s, but the writers had come to grips with what they were trying to do. The result was a more polished and sophisticated treatment.

No other editor gave writers this kind of opportunity on such a scale. The next closest was Ejler Jakobsson at GALAXY and IF and since those titles retained their formidable reputations from their former editors Frederik Pohl and Horace Gold, and were able to pay better word rates, they are often regarded as the leading experimental titles of the 1970s. But Jakobsson was not as proactive as White, nor did he have the same passion for the field. Neither GALAXY nor IF, for my money, was able to generate the energy that was sparking from AMAZING and FANTASTIC or the feeling that it was in their pages that things were happening.

There is a simple but original example of this fact. In the April 1970 FANTASTIC, Hank Stine wrote perceptive reviews of THE PRISONER television series and of the two novelizations from Ace Books, THE PRISONER by Thomas Disch and NUMBER TWO by David McDaniel. He considered the merits of leading writers adding other books to the series. Terry Carr, the editor at Ace, noted Stine’s views and commissioned him to do a third book in the series, A DAY IN THE LIFE. It was that kind of event that made one feel AMAZING and FANTASTIC were making things happen.

The same April 1970 FANTASTIC was significant for another reason: it carried the first new cover that White was able to commission, doing away with the European reprints. The May AMAZING followed suit. Thereafter White was able to publish some striking covers by some of the field’s most exciting artists: Jeff Jones, Mike Kaluta (FANTASTIC), John Pederson, Jr., Joe Staton (FANTASTIC), Doug Chaffee (FANTASTIC), Vaughn Bode, Dan Adkins, and most significantly Mike Hinge. Hinge’s covers were bold, brash, experimental, and colorful. They were called the science-fiction field’s first psychedelic covers, and they helped confirm the image AMAZING was building. Ironically, Hinge’s style had not been adapted for the 1970s. He had submitted some of these covers to AMAZING in the early 1960s, but the art editor had rejected them. Now, ten years later, they were finding their home at last. Hinge’s work was noted and appreciated. In 1973 he was nominated for the Hugo as Best Artist, losing out to Kelly Freas.

The same April 1970 FANTASTIC was significant for another reason: it carried the first new cover that White was able to commission, doing away with the European reprints. The May AMAZING followed suit. Thereafter White was able to publish some striking covers by some of the field’s most exciting artists: Jeff Jones, Mike Kaluta (FANTASTIC), John Pederson, Jr., Joe Staton (FANTASTIC), Doug Chaffee (FANTASTIC), Vaughn Bode, Dan Adkins, and most significantly Mike Hinge. Hinge’s covers were bold, brash, experimental, and colorful. They were called the science-fiction field’s first psychedelic covers, and they helped confirm the image AMAZING was building. Ironically, Hinge’s style had not been adapted for the 1970s. He had submitted some of these covers to AMAZING in the early 1960s, but the art editor had rejected them. Now, ten years later, they were finding their home at last. Hinge’s work was noted and appreciated. In 1973 he was nominated for the Hugo as Best Artist, losing out to Kelly Freas.

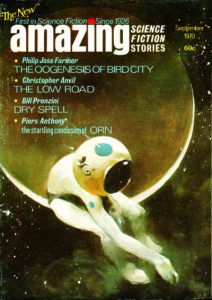

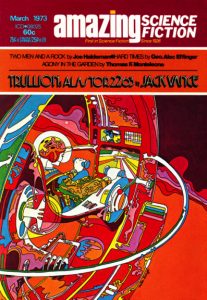

White’s credo had been to publish the best of the new alongside the best of the traditional. The emphasis was clearly on the new, and this was in part reflected by the change in the magazine’s full name from AMAZING STORIES to AMAZING SCIENCE FICTION STORIES (in September 1970) and then to AMAZING SCIENCE FICTION (in March 1972). There was also a restyling of the cover logo, giving a sharper, more contemporary 1970s image.

While White was publishing experimental work from more challenging writers, he was also nurturing new talent and welcoming back to the fold some of the older writers.

One of the first newcomers was Gordon Eklund. He appeared with “Dear Aunt Annie” in that all-important April 1970 FANTASTIC, and that story went on to be nominated for a Nebula Award as one of the year’s best novelettes. Eklund became one of the best new writers of the 1970s, his stories frequently presenting a fresh face on old themes. White was able to publish some of Eklund’s most thought-provoking works, including “Beyond the Resurrection” (FANTASTIC, April and June 1972), “The Ascending Aye” (AMAZING, January 1973), “Moby, Too” (AMAZING, December 1973), and “Locust Descending” (FANTASTIC, February 1976).

Other new writers whom White developed and encouraged included Gerard F. Conway, Grant Carrington, George Alec Effinger, F. M. Busby (who sold his first story in 1957, then waited fifteen years before selling his second one to White), Dennis O’Neil, Rich Brown, Janet Fox, Thomas Monteleone, and John Shirley. Not too surprisingly, most of these names first appeared in FANTASTIC, since that magazine allowed for a broader range of fiction with a greater opportunity to experiment. Shirley’s work, though, to a large extent typified what was appearing in AMAZING. His ‘What He Wanted” (AMAZING, November 1975) contains it all — sex, drugs, religion, violence, uncensored language, and rock and roll.

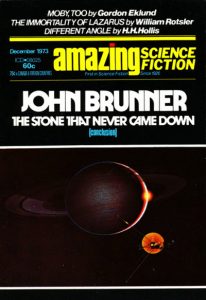

White also published new work by some of the old-timers in the field, such as Raymond Z. Gallun and Ross Rocklynne, as well as some not seen for years, such as Wilmar Shiras, Gardner F. Fox, and Noel Loomis. Alongside these he used some of the best work by leading writers: Bob Shaw, John Brunner, Brian Aldiss, Fritz Leiber, L. Sprague de Camp, Poul Anderson, Robert Silverberg, William F. Nolan, and Jack Vance.

The strength of both AMAZING and FANTASTIC was in their powerful lead novels supported by a genuine variety of exciting stories.

FANTASTIC was in the forefront of the growth of interest in fantasy fiction, and though it never seemed to benefit from this event directly in terms of increased circulation, the magazine was highly influential, as a vehicle for developing fantasy. It published, for instance, a rare sword-and-sorcery novella by Dean R. Koontz, “The Crimson Witch” (October 1970), in what should now be a highly collectible issue; it used a new Elric story by Michael Moorcock, “The Sleeping Sorceress” (February 1972); and it printed one of the finest yet most overlooked fantasy novels of the 1970s, “The Son of Black Morca” by Alexei and Cory Panshin (April, July, and September 1973, published in book form as EARTH MAGIC). It also ran several new Conan stories by L. Sprague de Camp and Lin Carter.

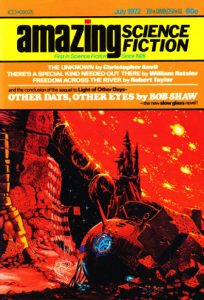

AMAZING was typified by its novels stressing the psychological anguish of the near future, works such as Silverberg’s “The Second Trip” (July and September 1971), about the effects of rehabilitating personalities; Shaw’s slow-glass serial “Other Days, Other Eyes” (May and July 1972); and Brunner’s savage future in “The Stone That Never Came Down” (October and December 1973), which considers the effects of a drug that enhances intelligence.

AMAZING was typified by its novels stressing the psychological anguish of the near future, works such as Silverberg’s “The Second Trip” (July and September 1971), about the effects of rehabilitating personalities; Shaw’s slow-glass serial “Other Days, Other Eyes” (May and July 1972); and Brunner’s savage future in “The Stone That Never Came Down” (October and December 1973), which considers the effects of a drug that enhances intelligence.

Although there were also more traditional stories in AMAZING, on balance the majority emphasized the social and cultural aspects of the future rather than the scientific. They also showed a tendency toward emphasizing sex in all its forms (you were probably wondering when I would get to that part of the title). White didn’t deliberately buy sex stories for effect, though some writers may have produced work with that intent, but there was no doubt that as the 1970s progressed, and as the barriers around the free use of sex in science fiction came down, so the topic began to dominate stories, and those in AMAZING perhaps more than those in other magazines.

There are a few that stand out. White got the ball rolling (if you’ll excuse the expression) with some of his own stories, which had been rejected from Harlan Ellison’s DANGEROUS VISIONS anthology. “Growing Up Fast in the City” (May 1971) looked at the lives of students in the near future, and involved some scenes of loose sex. By today’s standards these scenes were mild, but they brought a hostile response from some readers, who regarded the story as pornographic. It was nothing compared to what lay in the future. Other offerings included several short stories by Barry Malzberg that seem to have no motive in mind other than to shock. “On Ice” (January 1973) involves a drug-induced frenzy leading to a climax of buggery and possession, while “Upping the Planet” (April 1974) concerns a man having to masturbate twenty-four times in twenty-four hours in order to save the planet from alien invasion.

But the most controversial of all was “Two of a Kind” by Rich Brown (March 1977). Set in an anarchic future where government agents hunt down blacks for meat and sport, the story is taken up in great part by the graphic rape of a black woman and the slaughter of her rapists. Apart from the futuristic setting and some of the sf trappings — laser guns and field suits — this story could easily be set in the modem day, and reads like an excuse for sex and violence.

Controversy aside — though it was never far away in White’s magazines — White published much that was respectable science fiction and fantasy. For instance, “Junction” by Jack Dann (FANTASTIC, November 1973), about a small midwestern town separated from causality and surrounded by chaos. Or “The Cliometricon” (AMAZING, May 1975; reprinted in August 1991), one of George Zebrowski’s ingenious stories about a history machine. Or “His Hour Upon the Stage” (AMAZING, March 1976), a telling story about the last live actors by Grant Carrington. Or “Tin Woodman” (AMAZING, December 1976), a delightful first-contact story by Dennis Bailey and Dave Bischoff. These last two mentioned stories were finalists for the Nebula Award.

Controversy aside — though it was never far away in White’s magazines — White published much that was respectable science fiction and fantasy. For instance, “Junction” by Jack Dann (FANTASTIC, November 1973), about a small midwestern town separated from causality and surrounded by chaos. Or “The Cliometricon” (AMAZING, May 1975; reprinted in August 1991), one of George Zebrowski’s ingenious stories about a history machine. Or “His Hour Upon the Stage” (AMAZING, March 1976), a telling story about the last live actors by Grant Carrington. Or “Tin Woodman” (AMAZING, December 1976), a delightful first-contact story by Dennis Bailey and Dave Bischoff. These last two mentioned stories were finalists for the Nebula Award.

Like them or loathe them, you could never ignore the stories in AMAZING, and they made every issue an event. And let me not mislead you. I’ve concentrated on the fiction, but White also did much to make the nonfiction departments in both magazines lively and informative. Right from the start he had reinstated “The Club House,” reviewing fan publications, run by John D. Berry initially and later by Susan Wood. There was a long and lively letters section, and a wide range of perceptive book reviews. White’s editorials were always fascinating, if at times self-indulgent. And there were always interesting pieces on subjects relevant to sf, such as Greg Benford’s series of articles and Darrell Schweitzer’s author interviews.

White’s success was not ignored by the fans. AMAZING was nominated three times for the Hugo Award for Best Professional Magazine (1970, 1971, and 1972), each time coming in third behind F&SF and ANALOG. When that category was discontinued in favor of Best Professional Editor, White was nominated every year from 1973 through 1977, though he never finished higher than third.

But this recognition was not reflected in sales. Despite all he did to make AMAZING and FANTASTIC the most exciting magazines of the 1970s, circulation continued to dwindle. AMAZING‘s sales had been around the 38,000 mark when White took over in 1968. It dropped a thousand or two per year, so that by 1978 it was down to 22,000. White grew increasingly more frustrated with this trend. Early in his editorial reign he had argued that he was seeking to make AMAZING the best magazine on the market, and only if that achievement led to no increase in circulation would he concede that he had failed.

But is a rise or fall in circulation necessarily related to quality? We’ve already seen how AMAZING‘s circulation rose rapidly in the 1940s in response to the Shaver Mystery. So when AMAZING‘s quality was at its lowest ebb, circulation was at its highest. When AMAZING redeemed itself under Cele Goldsmith in the early 1960s, circulation continued to fall. Yet, when Sol Cohen purchased it and instigated his reprint policy, circulation initially rose. Now, when White had made AMAZING arguably one of the most important science-fiction magazines, circulation was dropping.

But is a rise or fall in circulation necessarily related to quality? We’ve already seen how AMAZING‘s circulation rose rapidly in the 1940s in response to the Shaver Mystery. So when AMAZING‘s quality was at its lowest ebb, circulation was at its highest. When AMAZING redeemed itself under Cele Goldsmith in the early 1960s, circulation continued to fall. Yet, when Sol Cohen purchased it and instigated his reprint policy, circulation initially rose. Now, when White had made AMAZING arguably one of the most important science-fiction magazines, circulation was dropping.

Clearly it was not White’s failure. Other science-fiction magazines were similarly suffering. IF had folded in 1974, and GALAXY would barely survive the decade. Other seemingly strong new titles, among them COSMOS and VERTEX, came and went. Who or what was to blame?

It is easy to blame the distributor. Over the years, weak distribution has caused the death of scores of magazines. AMAZING was selling only a third of the copies it printed. Two-thirds, therefore, either were languishing in the distributor’s warehouse or remaining boxed and unopened at the newsstand. Crazy though this may seem, it was probably more profitable for the distributor and dealer to act this way, since they were guaranteed money on returns. AMAZING suffered from not being big enough (like PLAYBOY or TIME) to make wholesale distribution profitable or small enough (like some of the emerging small-press magazines, such as WHISPERS) to survive solely by subscription.

There was another factor to consider: the changing shape of the science-fiction market. Magazines had been in decline since the 1950s, under threats from television, comic books, and paperbacks. Those threats had not gone away by the 1970s. However, although television had eaten into reading time (and may have totally taken away the desire to read in some people), it was not a substitute for reading. Comic books attracted the more junior element of the magazine readership, one to which AMAZING was no longer trying to appeal. So the most direct threat was from the paperback book.

The most popular paperback books were novels, and one way that magazines fought against this phenomenon was by advance serialization of novels. But with paperback novels now proliferating, this feature of magazines was becoming less of a lure to readers.

The magazine’s main territory was the short story. Book publishers have always maintained that short-story collections do not sell as well as novels, yet that has not stopped their regular publication. Science-fiction anthologies have frequently sold well, but until the 1960s they contained mostly stories reprinted from magazines. Magazines retained the strength of being the place where new short stories could be seen. Then, that bastion was eroded away during the 1970s. The previous decade had seen the birth of a number of regular paperback anthologies, with NEW WRITINGS IN SF and ORBIT leading the way. The 1970s brought a proliferation of these series: NOVA, NEW DIMENSIONS, UNIVERSE, QUARK, INFINITY, plus a mass of original anthologies edited by Roger Elwood. By the mid-1970s the short-story market was saturated. The magazines, always playing second fiddle to the paperbacks, were bound to suffer.

The magazine’s main territory was the short story. Book publishers have always maintained that short-story collections do not sell as well as novels, yet that has not stopped their regular publication. Science-fiction anthologies have frequently sold well, but until the 1960s they contained mostly stories reprinted from magazines. Magazines retained the strength of being the place where new short stories could be seen. Then, that bastion was eroded away during the 1970s. The previous decade had seen the birth of a number of regular paperback anthologies, with NEW WRITINGS IN SF and ORBIT leading the way. The 1970s brought a proliferation of these series: NOVA, NEW DIMENSIONS, UNIVERSE, QUARK, INFINITY, plus a mass of original anthologies edited by Roger Elwood. By the mid-1970s the short-story market was saturated. The magazines, always playing second fiddle to the paperbacks, were bound to suffer.

Ironically, against this background came a successful new magazine. ISAAC ASIMOV’S SCIENCE FICTION MAGAZINE, under the editorship of George Scithers (who steps into AMAZING‘s history in our final article), was issued in January 1977. Its circulation immediately exceeded 100,000, four times that of AMAZING and more than that of ANALOG, the former leader in the field.

Of course, the new magazine had the selling power of Asimov’s name, but it had more than that. Its publisher, Joel Davis, believed in digest fiction magazines and was solidly behind their promotion. He was able to market ASIMOV’S alongside the bestselling ELLERY QUEEN MYSTERY MAGAZINE, and the new periodical clearly benefited from a combined distribution package. The irony here is that Joel Davis is the son of Bernard Davis, the co-publisher of AMAZING during its Ziff-Davis days. Bernard Davis had left that firm in 1957 when it started to move away from fiction magazines. If he had taken AMAZING with him, the magazine’s fate may have been oh so different.

All these factors were affecting Ted White. He was becoming tired. His editorial work had always been a part-time job, yet it was growing increasingly more time-consuming as he took on further responsibilities not just in editing but in art design and packaging. The demands of his expanding role were dominating and sapping his writing energies. He occasionally vented his views in his editorials, and in so doing sometimes clashed with his publisher. Although Sol Cohen was the active partner in the Ultimate Publishing Company, the financing for the magazine came from Arthur Bernhard, who did not always like the political views expressed by White. More than once, White had to pull an editorial that had been vetoed by Bernhard.

Money was always tight. White introduced a controversial new policy whereby unsolicited submissions from writers with no previous sales had to be accompanied by a twenty-five-cent reading fee, which went to AMAZING‘s first readers, Grant Carrington and Rick Snead. While many people recognized the value in such a tactic, it was overall an unpopular move, since it was effectively aimed against the very writers White was seeking to encourage. It was a sign of desperation.

Several times Cohen sought a new publisher for the magazine, but Bernhard vetoed any sale. White became increasingly fatigued, and considered resigning in 1975. Then came a change in the publishing schedule. Cohen was especially concerned when a price increase from 75¢ to $1 (November 1975) caused sales to drop alarmingly. He decided to let issues stay on sale a month longer in hopes of recouping the lost market, and so both AMAZING and FANTASTIC went to a quarterly schedule. This allowed White more time to edit each issue, so he stayed on. However, this change also made it impractical to run serials. As a consequence, another of AMAZING‘s weapons against the paperback was lost.

Sales continued to drop. In September 1978, Cohen called it a day. He was sixty-eight, and he was also tired. He sold his stock to Bernhard, who took over full control of the magazines. White agreed to stay on during the transition, but six weeks later he resigned. By then it had become clear that Bernhard did not intend to invest any new money in the magazines. The stories in the inventory had not been paid for, and White returned them to their authors, suggesting they may choose to resubmit them to the new publisher.

White had had enough. He had remained true to the spirit of the magazines throughout his ten years as editor, second only to Palmer in duration. (In fact, his period exceeds Palmer’s if you exclude Palmer’s final two years, when William Hamling was really editing the magazine.) The final issues lacked some of the verve of White’s early years, not surprising considering the pressures he was facing. Against the most appalling odds, White had achieved the impossible. He had rescued AMAZING from its fate in 1968, had given it a respectability and reputation that was enviable, and had furthered the evolution of science fiction during one of the genre’s most volatile decades. It was probably the right time to move on. (White eventually became editor of the fantasy graphic magazine HEAVY METAL, and thereafter developed his own music label. We end where we began, with the power of music.) But the magazine needed a good editor to take up the reins.

White had had enough. He had remained true to the spirit of the magazines throughout his ten years as editor, second only to Palmer in duration. (In fact, his period exceeds Palmer’s if you exclude Palmer’s final two years, when William Hamling was really editing the magazine.) The final issues lacked some of the verve of White’s early years, not surprising considering the pressures he was facing. Against the most appalling odds, White had achieved the impossible. He had rescued AMAZING from its fate in 1968, had given it a respectability and reputation that was enviable, and had furthered the evolution of science fiction during one of the genre’s most volatile decades. It was probably the right time to move on. (White eventually became editor of the fantasy graphic magazine HEAVY METAL, and thereafter developed his own music label. We end where we began, with the power of music.) But the magazine needed a good editor to take up the reins.

I was horrified when I saw the May 1979 AMAZING, the first under Bernhard’s new regime. Because of a lack of new material, the issue was mostly reprints. The production was awful. It looked cheap and uninspiring. That horrible feeling of déjà vu swept over me. I rushed off a letter to the new editor, someone called Omar Gohagen, saying, more or less, “My God. What have you done?”

Just what they had done, and how AMAZING survived into the twenty-first century, we’ll explore in the final installment of this series appearing on Thursday, March 10th.

“The AMAZING Story: The Seventies — Sex and Drugs and Rock and Roll” is © 2016 by Mike Ashley and appears here with the author’s permission. Notes in italics are by PulpFest and are © 2016 by PulpFest. The original article was published by TSR, Inc. and edited by Kim Mohan for the June 1992 issue of AMAZING. Many thanks to Curt Phillips, the moderator of the Yahoo newsgroup PulpMags, for drawing our attention to and providing us with copies of Mike Ashley’s exceptional series of articles about the world’s first science-fiction magazine. Please visit pulpcon.org on Thursday, March 10th, for the seventh and final segment of the series.

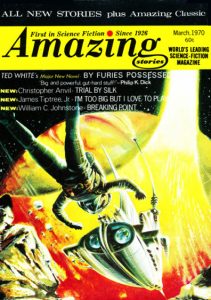

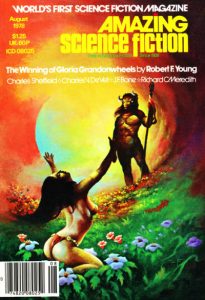

(Concerning our illustrations . . . . Ted White succeeded Barry Malzberg as the editor of AMAZING STORIES in October 1968. A longtime science fiction fan, White’s first issue was dated May 1969. Except for an Edmond Hamilton novella (previously unpublished in English); a vignette by Ray Russell; and some non-fiction articles, the contents of the issue consisted of reprints from 1950s issues of AMAZING. The cover art — by an unknown artist — was also a reprint. It came from the PERRY RHODAN series and was originally published in Germany.

The first six issues of White’s AMAZING all featured cover art reprinted from the German PERRY RHODAN book series. This included the March 1970 number which featured a cover painting by an artist named “Willis.” It had originally appeared on PERRY RHODAN #201. However, aside from the cover and a Dr. David Keller story from 1933, everything else in the issue was new, including the first half of White’s own novel, “By Furies Possessed,” one of the author’s finest works.

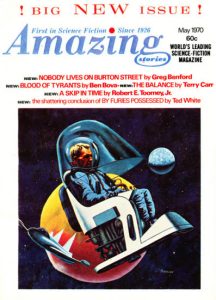

Because Ted White was paying the lowest rates in the field, he knew he wouldn’t be able to acquire the best fiction around, but he might have a chance at some of the best experimental fiction, created by authors who had no ready market elsewhere. He did much the same with his AMAZING cover artists, publishing some striking covers by visual artists such as Tom Barber, Vaughn Bode, Don Davis, Stephen Fabian, Mike Hinge, Jeffrey Jones, Larry Todd, and John Pederson, Jr., whose front cover for the May 1970 AMAZING STORIES was the first original cover painting for White’s magazine. Pederson would paint a half dozen covers for AMAZING and its companion. He also contributed covers to GALAXY, IF, THE MAGAZINE OF FANTASY & SCIENCE FICTION, and WORLDS OF TOMORROW.

As editor of AMAZING, Ted White sought to publish the best of the traditional alongside the best of the new, with the emphasis clearly on the new. This was aptly demonstrated when the magazine’s name was changed to AMAZING SCIENCE FICTION STORIES in September 1970. There was also a restyling of the cover logo, making it sharper and more contemporary. It fit well with Jeffrey Jones‘s first cover painting for the magazine, one of nine he would create for AMAZING and FANTASTIC. A largely self-taught artist, Jones’ earliest professional work appeared in James Warren’s CREEPY and EERIE. Soon thereafter, he started to paint paperback covers for a wide variety of publishers including Ace, Berkley, Centaur, Dell, Fawcett, Lancer, Pyramid, and Zebra. In later years, Jones concentrated on gallery work, prints, and portfolios.

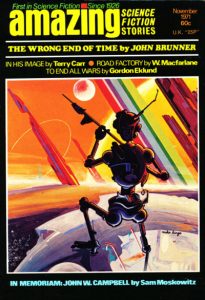

Perhaps the artist who best reflected White’s use of the traditional alongside the modern was Mike Hinge. This idea is aptly reflected by the artist’s cover for the November 1971 AMAZING SCIENCE FICTION STORIES. Hinge’s covers were bold, brash, experimental, and colorful. They were called the science-fiction field’s first “psychedelic covers” — well demonstrated by the artist’s cover for the March 1973 AMAZING SCIENCE FICTION — and helped to identify AMAZING as the “hippie” science-fiction magazine. A native of New Zealand, Hinge emigrated to the United States in 1959, finding work as an advertising artist. A leading science fiction fan in his homeland, he renewed his relationship with fandom after moving to New York City in 1966. In addition to his work for Ted White’s magazines, he also created cover art for ALGOL, ANALOG, books and other magazines.

AMAZING was typified by its novels stressing the psychological anguish of the near future, including works such as Bob Shaw’s serial “Other Days, Other Eyes,” which ran in the May and July 1972 issues of the magazine. The latter number featured one of Larry Todd‘s covers, based on a color sketch by Vaughn Bode. Todd and Bode collaborated on three covers for AMAZING as well as one for FANTASTIC. Primarily known as underground comic book artists, Todd is best remembered for Dr. Atomic (which ran in LAST GASP COMICS) while Bode is best known for Cheech Wizard (which ran in NATIONAL LAMPOON). Todd also contributed cartoons to IMAGINATION, GALAXY, WORLDS OF TOMORROW, and other science-fiction magazines. Bode contributed a substantial number of interior illustrations to GALAXY and IF during the late sixties. He also painted covers for GALAXY, IF, and THE MAGAZINE OF FANTASY & SCIENCE FICTION.

John Brunner’s “The Stone That Never Came Down” was another AMAZING novel of near future angst. It was serialized in the October and December 1973 issues. The closing segment featured front cover art by Don Davis, an illustrator who created three covers for the magazine. Primarily a space artist who worked for the United States Geological Survey and NASA, Davis also created a few covers for ALGOL, AMAZING, THE MAGAZINE OF FANTASY & SCIENCE FICTION, VERTEX, and Larry Niven’s RINGWORLD.

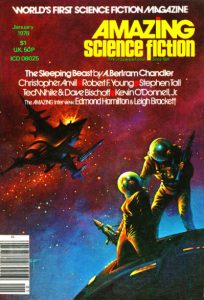

Although Ted White’s AMAZING was nominated three times for the Hugo Award for Best Professional Magazine and White himself was nominated five times as Best Professional Editor, the magazine’s circulation continued to decline throughout White’s term editorial reign. Despite all he did to make AMAZING and FANTASTIC the most exciting magazines of the 1970s — including adding Stephen Fabian to his list of cover artists — the two digests continued to lose readers. Fabian’s exotic and dramatic covers were featured on nine issues of AMAZING — including the January and August 1978 numbers — and 11 issues of FANTASTIC.

A former associate engineer in the electronics industry, Stephen E. Fabian taught himself to illustrate by studying art books and practicing. After losing his engineering job, he began contributing illustrations and covers to AMAZING, FANTASTIC, GALAXY, IF, and other magazines; small press publications such as CRYPT OF CTHULHU, WEIRDBOOK, and WHISPERS; and independent book publishers including Donald M. Grant, Gerry De La Ree, Starmont House, Underwood-Miller, and Wildside Press. He has been nominated for numerous Hugo and World Fantasy Awards and has won the British Fantasy Award for best professional artist.

In 1975, Ted White resigned as editor of AMAZING and FANTASTIC. He explained his reasons in Richard Geis’s SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW:

I am tired of editing two magazines which limp from month to month on the inadequate budget and over-extended energies of a very few people. I have edited AMAZING and FANTASTIC for more than six years . . . my energies are depleted. I am paid a literal pittance to get these magazines out, I am perennially late with deadlines, and to a great extent they have become a minimally subsidized hobby.

When I began with the magazines I brought to them a lot of energy and enthusiasm and a great many ideas for their improvement . . . Well, I have put into effect nearly every idea which I was allowed to follow through on . . . and I have spent most of my energy and enthusiasm.

Thankfully, Sol Cohen was able to convince White to stay with the magazines for three more years, but AMAZING and FANTASTIC continued to lose readers. By 1977, they were losing money. After Cohen sold his stake in the company, Ted White resigned his position. White’s final issue of AMAZING was dated February 1979 and featured cover art by Tom Barber (who painted four covers for the magazine). Barber was active in the field during the late seventies and early eighties, painting covers for AMAZING, GALILEO, HEAVY METAL, and WEIRD TALES. He also contributed paperback covers to DAW and Zebra Books.)